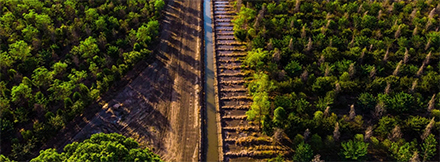

The world’s second-biggest producer of Indian sandalwood has completed its largest ever commercial harvest in Western Australia’s remote Kimberley region. More than 106 hectares of timber has been put through Santanol’s processing shed in Kununurra, where the sweet scent of sandalwood wafts through the air as it is dried, graded, and fed through grinding equipment. Source: ABC News

From there the processed chips are trucked more than 3000 kilometres south to the company’s facility in Perth, where the sandalwood oil will be distilled and refined over the next 12 months.

Santanol managing director David Brocklehurst said after many years spent trying to perfect its forestry model, this was the company’s most important harvest yet.

“This is one of our very early plantations,” he said. “They were still learning the art of growing sandalwood, so for so many of our trees to have that much heartwood is really encouraging.

“The results from this will be incredibly valuable for us across the balance of the estate and how we manage it moving forward.”

The Indian sandalwood producer, which was bought by global forestry giant Mercer International in 2018, owns more than 2000ha of trees across the Ord Irrigation Scheme.

Over the past four years the company has been selling its Santalum album oil to fine fragrance markets in Europe, North America, the Middle East, India, and China.

Often described as “liquid gold”, nearly half of all perfumes contain sandalwood oil.

Mr Brocklehurst said sales had been growing rapidly, but the harvest milestone came at a challenging time for the global perfume industry.

“We can only hope that COVID-19 goes away, because the fine fragrance industry has been severely impacted by lack of travel around the world,” he said.

“I think prices for sandalwood will stay stable for now … it’s a very consistent product from a perfumer’s perspective, but other essential oils are a quarter of the selling price they were 12 to 18 months ago.”

Closer to home, the Indian sandalwood industry in Kununurra weathered some turbulent times after Santanol’s major competitor, Quintis, fell into administration and recapitalised as a private company in 2018.

Since then the company has resumed harvest operations and completed a product rebrand, all the while defending multiple lawsuits and an attempted takeover of several Quintis-managed sandalwood plantations.

Santanol has been through some organisational changes of its own following its acquisition by the NASDAQ-listed Mercer, with outgoing Paris-based chief executive Remi Clero stepping down earlier this year.Mr Brocklehurst has managed forestry and distillery operations from the company’s Perth headquarters since February, bringing more than 20 years of experience from the native sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) industry.

“Western Australia is the global heart now for the production of sandalwood oil, whether it be spicatum or album,” he said.

“There are similarities with forestry but they’re very distinct product and each have their own place in the market.

“From an [Indian sandalwood] oil perspective, you’re well over $US100,000 per tonne — compared to something like blue gum chips, it’s very much a ‘Rolls Royce’ item.”It has been a bumpy road for the Indian sandalwood industry over the years, but Mr Brocklehurst is convinced there is a bright future ahead.

“I guess with an increase in production overseas … it’s likely prices will back off a little bit, maybe, over the next three to five years, but there’ll still be a good return,” he said.

“There are new applications being worked on by companies in different areas — cosmeceuticals in particular, we hope to see that broaden and expand too.”

Santanol will resume harvesting at its Kneebone plantation in Kununurra next April, although the size of the harvest will depend on the recovery of global oil demand.

Mr Brocklehurst said the company was also committed to planting more acreage and improving the sustainability of operations by reducing insecticide use and producing biochar from old host trees to improve soil health.

He said the company had come a long way since a failed experiment that saw several of early plantations established without accompanying host trees.

“It is tricky … with a crop like sandalwood you have to have a commitment and you have to have deep pockets, but if everything goes well, the returns are very solid,” Mr Brocklehurst said.

“Yes, you’ve got to be very patient, there’s certainly no doubt about that, but it gets into your blood … I can’t imagine doing anything else really.”