Australia’s pipeline of homebuilding activity is at record levels and growing at its fastest ever pace. Already besieged by literally unprecedented demand, the entire building supply chain is short of the materials and the labour it needs to meet the stimulus-fuelled demand. For Australia’s timber and wood products industry, the pressure is all the more significant because demand for sustainable building products has never been greater, and the pressures on the local supply chain have rarely been as severe. Source: IndustryEdge

The following summary was prepared by IndustryEdge’s Managing Director Tim Woods, based on two recent industry presentations and a detailed housing pipeline analysis conducted by the company, in conjunction with the Frame & Truss Manufacturers’ Association of Australia (FTMA).

At IndustryEdge, we undertake analysis of Australian housing markets because housing is the primary demand driver for the timber and wood products industry.

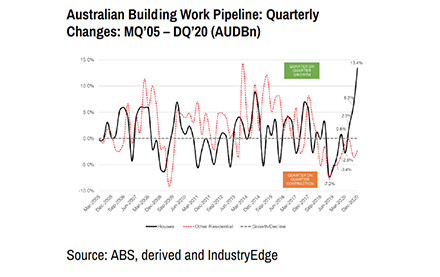

Work our team conducted in the early part of 2021 pointed to a pipeline of building work that was getting out of control.

Our view, informed by publicly available evidence and confirmed by client experience, was that the pipeline of work – that is, work that has been approved, financed or has commenced and is not completed – was causing demand-side pressures that were impossible for the supply chain to resolve.

Unlike previous spikes in the size of the pipeline of work, we could not find the end to this boom.

The reasons are important to understand.

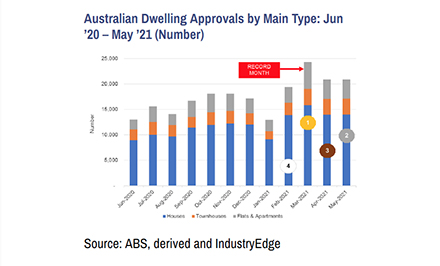

Almost the entire explosion in housing approvals has been in free-standing houses, not townhouses and certainly not flats and apartments. That ‘skew’ towards houses alters the balances in the building supply chain, impacting where the building work occurs, what materials are required, and the type of labour required.

Let’s explore that a bit further:

- Instead of the work being spread across our vast and sprawling cities, it is – for the new work – pocketed in our outer suburbs, where there is the space to build new houses on their own block of land. Freight, logistics and labour transport friction is at its worst at the furthest extremities of our typical ‘hub and spoke’ cities. The further out you build, the less efficient the system can become, on average at least.

- Houses – and to a lesser extent, townhouses – are made from timber and wooden building products for the most part. In an ordinary housing market spike, demand would be spread across formats that involve greater influence from the less sustainable building products: concrete and steel come to mind, of course. When the expansion is largely constrained to free-standing houses, the additional pressure is disproportionately landed onto timber and wood products. No one needs us to describe the gap between demand and supply right now! There is a close correlation between house approvals and structural timber consumption in Australia. Each new house adds almost a full unit of structural timber consumption.

- Equally important, specialisation of construction industry labour is not new. Specialisation has its advantages, but it also means skills do not transfer as well from one sector to the next. Sure, a construction carpenter with skills in building formwork can shift to the housing sector, but can they install frames, align trusses, fix windows and doors and the myriad other housing tasks as easily as an established house carpenter? Likely not, and vice versa of course.

So, the rapid uplift in approvals for new houses and building work on those houses, compared with all other housing formats, brings with it some really significant ‘friction’. That gets worse if more work is added to the pipeline, and ultimately, it can only be resolved with the passage of time.

In this chart, we can see how the pipeline of work grew at record levels (up 13.4% in value terms) in the December quarter (the latest formal data), recording the third successive quarter of pipeline growth for houses and houses alone. A massive amount of work was added to the pipeline in the December quarter alone –and the pipeline was already overflowing.

For the timber and wood products industry and its supply chain, it is great to have so much work to do on houses, but when the ‘ramp rate’ has been so steep, itis impossible to keep up. That has caused observable and extensive stress across the supply chain.

Until recently, IndustryEdge considered that the market might come back into balance early 2022. That is, we thought building work would be at a level to keep the supply chain under pressure, but that at that point, supply of timber would keep pace from then on.

The most recent housing approvals data demonstrates that we were wrong.

It proves the current pipeline of building work is out of control and is running unrestrained through the nation, like a proverbial bull in a china shop.

Further, latest evidence shows the housing pipeline situation will get worse in coming months, prolonging the demand-side pressures on timber supply until mid-2022 at the most optimistic assessment. But, as each month passes, that projection pushes out further. Lets say now, the overhang of work and an excess of demand for timber will probably be running until sometime in 2023.

The evidence? The last four months of approvals for new free-standing house approvals are the four highest single months of approvals ever.

It is, in that context, ironically fitting that 2021 has become an Olympic year, because Australian housing approvals are breaking all the records right now. In addition, March saw the highest total level of approvals ever. What this current situation means is that each month, the pipeline is being extended by more than one month, the pressures of existing demand are compounded by the additional demand and the end of the over-hang of work is pushed further into the distance.

This is weighing heavily on the supply chain as every builder, every fabricator and every homeowner demands priority for their job, regardless of how much other work is ahead of theirs in the pipeline. Sadly, timber supply is not a magic pudding. There simply is not enough timber available in the global supply chain, let alone locally, to meet demand.

Inevitably, we are being asked repeatedly right now: how long will the Australian building supply chain take to ‘build out’ the pipeline?

The short answer is that we do not know. But. here is what we do know.

Every month in which approvals of free-standing houses are greater than the long-term monthly average of around 11,000 per month, is adding more than one month of building work to the notional pipeline.

As the Australian economy moves to full employment (and that is not as far off as we might think), the potential additional capacity to do the work dries up. Couple that with zero net overseas migration for the last year and probably the next 18 months and there can be no additional capacity to push the pipeline of work through any faster.

Eventually though, the pipeline will be built out. The pent up demand will be satiated, there will be no new migrants who have formed households and have acquired the capacity to get a house of their own, and we can pretty much bet interest rates will be higher, given they are already starting to move up. What happens after housing booms, especially booms constructed using Government stimulus and low interest rates?

Well, let’s just say … the wise businesses and the smart households will prepare themselves for a downturn of ‘some magnitude’.